A new discovery takes plants’ deception of their pollinators to a whole new level. Researchers reporting in Current Biology on October 6 found that the ornamental plant popularly known as Giant Ceropegia fools certain freeloading flies into pollinating it by mimicking the scent of honeybees under attack. The flies find that smell attractive because they typically dine on the drippings of honeybees that are in the clutches of a spider or other predatory insect.

A new discovery takes plants’ deception of their pollinators to a whole new level. Researchers reporting in Current Biology on October 6 found that the ornamental plant popularly known as Giant Ceropegia fools certain freeloading flies into pollinating it by mimicking the scent of honeybees under attack. The flies find that smell attractive because they typically dine on the drippings of honeybees that are in the clutches of a spider or other predatory insect.

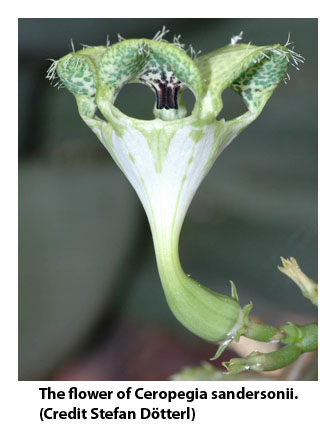

“These flowers have a complex morphology, including trapping structures to catch pollinators, temporarily trap, and finally release them,” says Stefan Dötterl of the University of Salzburg in Austria. “We show that trap flowers of this plantmimic alarm substances of western honeybees to lure food-stealing freeloader flies as pollinators. Flies are attracted to the flowers, expecting a meal, but instead of finding an attacked honeybee they are temporarily trapped in the non-rewarding flowers and misused as pollinators.”

About four to six percent of plants, including the fly-pollinated genus Ceropegia, are pollinated by deceit. They engage in false advertising by appearing to offer a reward, such as pollen or nectar, a mating partner, or an egg-laying site. The new study is among the first to describe a plant that achieves pollination by mimicking the scent of an adult carnivorous animal’s dinner.

Study co-authors Annemarie Heiduk and Ulrich Meve from the University of Bayreuth in Germany got curious when they realized that the flies pollinating Ceropegia sandersonii were Desmometopa. The flies are known as kleptoparasites, commonly feeding on honeybees eaten by spiders.

“We asked ourselves how the flies might find such honeybees,” Dötterl says.

When observing a honeybee caught by a spider, they noticed that the bee extrudes its sting and releases a drop of venom. The bees’ venom is known to contain volatile alarm pheromones, which serve to call and attract nest mates for help. They wondered whether the plant might be taking advantage of this line of communication among honeybees.

Preliminary experiments showed that honeybees under simulated attack are highly attractive to the flies. In the new study, the researchers show that the floral scent of C. sandersonii is indeed comparable to volatiles released from honeybees when under simulated attack. Some of those shared compounds also elicit a response in the antennae of pollinating Desmometopa flies and are strong attractants for these insects. The evidence is clear: an unusual blend of compounds emitted by C. sandersonii lures kleptoparasitic flies into the plants’ trap flowers.

T