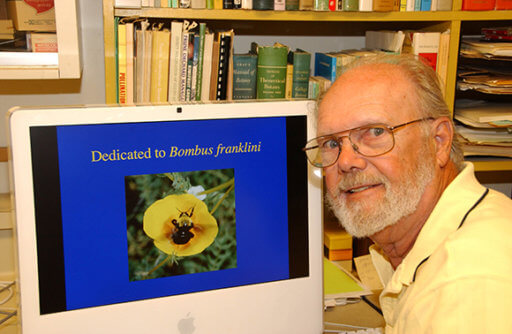

DAVIS – The late Robbin Thorp, distinguished emeritus professor of entomology at the University of California, Davis, and a global authority on bees, worked tirelessly to try to include Franklin’s bumble bee (Bombus franklini) as an endangered species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA).

In fact, he and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on June 23, 2010 to include the bumble bee on the proposed list.

Today (Aug. 14) the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed that it be listed as an endangered species. If approved, Franklin’s bumble bee would be the first bee in the western United States to be officially recognized under the ESA.

Its range, a 13,300-square-mile area confined to Siskiyou and Trinity counties in California; and Jackson, Douglas and Josephine counties in Oregon, is thought to be the smallest range of any other bumble bee in the world.

Thorp, who died at age 85 on June 7 at his home in Davis, had monitored the population closely since 1998, but last saw the bumble bee in August 2006. It was he who sounded the alarm.

Thorp’s surveys clearly show the declining population. Sightings decreased from 94 in 1998 to 20 in 1999 to 9 in 2000 to one in 2001. Sightings increased slightly to 20 in 2002, but dropped to three in 2003. Thorp saw none in 2004 and 2005; one in 2006; and none since.

He refused to believe that it may be extinct. “I am still hopeful that Franklin’s bumble bee is still out there somewhere,” he said late last year.

Xerces says that the primary threats to this species are three-fold:

- diseases from managed bees

- pesticides, and

- a small population size

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the world’s oldest and largest global environmental network, named Franklin’s bumble bee “Species of the Day” on Oct. 21, 2010. IUCN placed it on the “Red List of Threatened Species” and classified it as “critically endangered” and in “imminent danger of extinction.”

Franklin’s bumble bee, mostly black, has distinctive yellow markings on the front of its thorax and top of its head. It has a solid black abdomen with just a touch of white at the tip, and an inverted U-shaped design between its wing bases.

“This bumble bee is partly at risk because of its very small range of distribution,” Thorp related recently. “Adverse effects within this narrow range can have a much greater effect on it than on more widespread bumble bees.”

If it’s given protective status, this could “stimulate research into the probable causes of its decline,” said Thorp, an active member of the Xerces Society. “This may not only lead to its recovery, but also help us better understand environmental threats to pollinators and how to prevent them in future. This petition also serves as a wake-up call to the importance of pollinators and the need to provide protections from the various threats to the health of their populations.”

Thorp hypothesized that the decline of the subgenus Bombus (including B. franklini and its closely related B. occidentalis, and two eastern species B. affinis and B. terricola) is linked to an exotic disease (or diseases) associated with the trafficking of commercially produced bumble bees for pollination of greenhouse tomatoes. Other threats may include pesticides, climate change and competition with nonnative bees.

Named in 1921 for Henry J. Franklin, who monographed the bumble bees of North and South America in 1912-13, Franklin’s bumble bee frequents California poppies, lupines, vetch, wild roses, blackberries, clover, sweet peas, horsemint and mountain penny royal during its flight season, from mid-May through September. It collects pollen primarily from lupines and poppies and gathers nectar mainly from mints. According to a Xerces Society press release, bumble bees are declining throughout the world.

“The decline in bumble bees like Franklin’s bumble bee should serve as an alarm that we are losing important pollinators,” said Xerces Society Executive Director Scott Hoffman Black in a press release. “We hope that the story of the Franklin’s bumble bee will compel us to prevent pollinators across the U.S. from sliding toward extinction.”

Thorp, a member of the UC Davis entomology faculty for 30 years, from 1964-1994, achieved emeritus status in 1994 but continued to engage in research, teaching and public service until a few weeks before his death. A tireless advocate of pollinator species protection and conservation, he was known for his expertise, dedication and passion in protecting native pollinators, especially bumble bees, and for his teaching, research and public service. He was an authority on pollination ecology, ecology and systematics of honey bees, bumble bees, vernal pool bees, conservation of bees, native bees and crop pollination, and bees of urban gardens and agricultural landscapes.

In his retirement, Thorp co-authored two books Bumble Bees of North America: An Identification Guide and California Bees and Blooms: A Guide for Gardeners and Naturalists.

Born Aug. 26, 1933 in Benton Harbor, Mich., Robbin received his bachelor of science degree in zoology (1955) and his master’s degree in zoology (1957) from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He earned his doctorate in entomology in 1964 from UC Berkeley, the same year he joined the UC Davis entomology faculty. He taught courses from 1970 to 2006 on insect classification, general entomology, natural history of insects, field entomology, California insect diversity, and pollination ecology.

Every summer from 2002 to 2018, Thorp volunteered his time and expertise to teach at The Bee Course, an annual workshop sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History and held at the Southwestern Research Station, Portal, Ariz. The intensive 9-day workshop, considered the world’s premiere native bee biology and taxonomic course, is geared for conservation biologists, pollination ecologists and other biologists.

“Robbin’s scientific achievements during his retirement rival the typical career productivity of many other academic scientists,” said Steve Nadler, professor and chair of the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology, in the obituary on the department’s website. “His contributions in support of understanding bee biodiversity and systematics are a true scientific legacy.”